For four years, oil prices held steady at around $105 per barrel, however, prices started to decline sharply in the second half of 2014 and have continued to fall throughout this year. Several supply side reasons contributed to this price fall, including shale oil extraction, efficiency in hydrocarbons machinery and changes in OPEC objectives to maintain market share rather than target oil price bands. Most importantly, concerns about geopolitical factors disrupting the supply of oil from main exporters in the Middle East have contributed to the drop in oil prices.

European countries have, to varying degrees, enjoyed an economic boost thanks to reduce energy and transport prices. However, the other side of the story is the effect of the price drop on the fiscal balance of oil-producing countries in the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC).

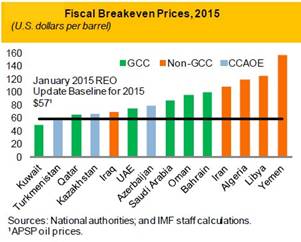

To better gauge the effect of the oil price fall on oil-exporting countries in the GCC, one needs to understand that huge losses are realised in varying degrees depending on whether or not the economies are highly dependent on oil exports. Oil export losses in 2015 are expected to reach about $300bn or 21% of GDP in the GCC and the oil price decline is likely to result in a fiscal deficit. Nonetheless, the vulnerability of oil-exporting countries is measured by ‘fiscal break-even prices’ – the oil prices at which the governments of oil-exporting countries balance their budgets. For GCC countries, the breakeven prices range from $54 per barrel for Kuwait to $106 per barrel for Saudi Arabia. Breakeven prices for 2015 are presented in the figure below – based on national authorities and International Monetary Fund figures.

On one hand, the sharp decline in oil prices have contributed to substantial volatility in equity markets as investors have started to reassess prospective growth rates for oil-exporting markets. On the other hand, the price decline has induced massive changes in oil subsidies and structural changes in taxation on the use of energy to counteract negative implications.

Budgetary constraints in oil-exporting countries are characterised as being ‘inevitable’. However, the policy changes in GCC countries manifest a true acknowledgement of the vulnerability inherent in oil-concentrated export strategies and the need to diversify the economy towards reliance on other sources of revenue.

Most GCC countries have significant fiscal buffers allowing them to avoid sudden cuts in spending while capitalising on real estate projects and services other than oil-based industries. For the less resilient economies, such as Bahrain and Oman, a reduction in fiscal expenditures is expected but over extended periods rather than immediately. The good news is that average buffers in GCC countries can finance substantial deficits for almost four years. Having the most diversified economy among all GCC countries, the UAE is estimated to grow its non-oil-based investments and thus might not need to make structural changes in its budgetary policies as the oil price drop has only marginal effects on growth rates. Likewise, Saudi Arabia and Qatar are in good financial position to cope with the falling oil prices.

Knowing that extreme cuts in fiscal expenditures might have serious effects on regional equity markets, policymakers take into account the importance of investor confidence and are therefore cautious not to communicate a negative image. Another option to investment diversification is debt issuance, especially Islamic financial instruments, which are now becoming popular in Europe, Asia, and the United States. Debt issuance doesn’t erode economic buffers and neither does it burden budgetary expenditures. In spite of declining oil prices, credit markets are solid, making debt issuance a promising path to follow.

GCC and emerging economies are still expected to grow, but at a slower pace. Budget cuts are painful and cannot be avoided. However, other solutions head towards the privatisation of non-essential public services and issuance of debt instruments. Potential sectors that are promising are banking, telecom, transportation, and aviation. The use of Islamic special purpose vehicles (SPV), to issue debt, remains an interesting and plausible route. The question now is not whether alternative routes can be used, but rather for how long they can sustain budgetary spending requirements given the declining price of the GCC’s black gold.